1Learning Outcomes¶

Translate between binary, decimal, and hexadecimal number representations

Use hexadecimal as shorthand for binary

Know when each representation is useful

🎥 Lecture Video

2Introduction¶

In this section, we discuss how computer architects and computer scientists translate between the rich world that humans see and information that computers store. The former is framed by how humans think—after all, we have ten fingers, also known as “digits”. The latter is in bits.

3Numerals as a representation of Numbers¶

Let’s discuss the idea of formally representing a number with many possible numerals, i.e., symbols.

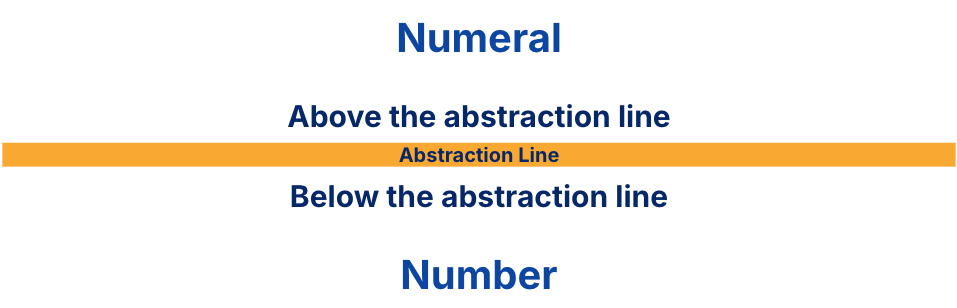

Numeral: A symbol (or series of symbols) or name that stands for a number, e.g., 4 , four , quatro , IV , IIII , …. Numerals are composed of multiple symbols called digits.

Number: The “idea” in our minds, e.g., the concept of “4”. There is only ONE concept of a number, but there can be many possible numeric representations via many possible numerals.

Figure 1:Numerals (and therefore digits) are representations of numbers.

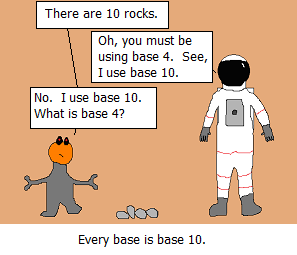

Figure 2 is a motivating (and humorous) example. An alien and an astronaut are discussing how to represent the number of rocks in a pile.

Figure 2:Every base is base 10 (web.archive.org)

The alien, the astronaut, and the pile of rocks use three different representations of the number four. The astronaut uses the numeral 4 to represent four as a base-10 integer. The alien uses the numeral 10 to represent four as a base-4 integer. The pile of rocks uses four rocks to represent four as, well, a pile of rocks.

4Binary, Decimal, and Hexadecimal Representations¶

While there are an infinite number of bases with which to represent numbers, we discuss three will be the most useful to us, as computer scientists: decimal, binary, and hexadecimal representations.

Table 1 probably makes little sense to you at the moment, but we present it first so you can make some educated guesses.

Table 1:Decimal, binary, and hexadecimal digits.

| System | # Digits | Digits |

|---|---|---|

| Decimal | 10 | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 |

| Binary | 2 | 0, 1 |

| Hexadecimal | 16 | 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, A, B, C, D, E, F |

4.1Decimal: Base 10 (Ten) Numbers¶

First, consider decimal numerals. The decimal numeral 3271 is written in that order, because it describes how to count powers of ten corresponding to the equation below (note the superscript 10 denotes a base-10 numeral):

Each of the four digits specify a count of a power of ten. We add these up to get the number three thousand, two hundred seventy-one.

Explanation

The rightmost digit, 1, corresponds to the smallest power of 10 that composes a non-negative integer. This is the zero-th power, or . We include one.

The next digit, 7, corresponds to the next smallest power of 10, which is , or ten. We include seven tens.

The next digit, 2, corresponds to the next smallest power of 10, which is , or one hundred. We include two hundreds.

The final leftmost digit, corresponds to the largest power of 10 for this number, which is , or one thousand. We include three thousands.

This process will seem natural to you—because we humans think in base ten—but we will see that we can apply this understanding to represent numbers in other bases. Nevertheless, we highlight a few implicit assumptions:

For now, we only consider powers of 10 needed to compose non-negative integers; we will discuss how to represent fractions later. The smallest such power of 10 is .

The “largest” power of 10 for this number can be more precisely defined as the largest power of 10 corresponding to a non-zero digit. In other words, the decimal with leading zeros (on the left) and the decimal 3271 represent the same number.

Base ten uses the ten digits

0to9to create unique decimal representations. In other words, to form the decimal 10, instead of using ten of 100, we use one 101 and zero 100. Wikipedia provides a more formal discussion of uniqueness.

4.2Base 2 (Two) Numbers, Binary¶

Binary numbers like 1101 are written in that order to describe how to count powers of two. Notably, the two binary digits, 0 and 1, are the namesake of the bit (which takes on those two values).

What does the binary numeral

1101represent?

Because humans think in decimal, we convert this binary value to decimal with a similar process as above:

Explanation

The rightmost digit, 1, corresponds to the smallest power of 2 that composes a non-negative integer. This is still the zero-th power, or . We include one one.

The next digit, 0, corresponds to , or two. We include zero twos.

The next digit, 1, corresponds to , or four. We include one four.

The final leftmost digit, 1 corresponds to , or eight. We include one eight.

Adding up one one, zero twos, one four, and one eight gives thirteen, or the decimal 13.

Other notes:

We prepend the prefix

0bto denote that the numeral1101should be interpreted in base 2; the shorthand0b1101is equivalent to the mathematical notation 11012 but can be written with a standard keyboard.Like before,

0b0...01101and0b1101represent the same nunber, thirteen.Because there are just two binary digits

0and1, in binary we are always either including a value (here, a specific power of two), or not including it.1or0,TrueorFalse. This idea of binary representing “inclusion” or “exclusion” will show up repeatedly in this course.

4.3Base 16 (Sixteen) #s, Hexadecimal¶

Finally, we consider hexadecimal numbers.

What does the hexadecimal numeral

A5represent?

Convert to decimal:

We prepend the prefix 0x to denote that the numeral A5 should be interpreted in base 16. Like before, the shorthand 0xA5 is equivalent to but can be written with a standard keyboard.

Hexadecimal digits are useful as shorthand for representing groups of four binary digits. We discuss more at the end of this section.

5Convert between representations¶

Table 2:First sixteen numbers as decimal, hexadecimal, and binary representations.

| Number | Hexadecimal | Binary |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0000 |

| 1 | 1 | 0001 |

| 2 | 2 | 0010 |

| 3 | 3 | 0011 |

| 4 | 4 | 0100 |

| 5 | 5 | 0101 |

| 6 | 6 | 0110 |

| 7 | 7 | 0111 |

| 8 | 8 | 1000 |

| 9 | 9 | 1001 |

| 10 | A | 1010 |

| 11 | B | 1011 |

| 12 | C | 1100 |

| 13 | D | 1101 |

| 14 | E | 1110 |

| 15 | F | 1111 |

Let’s discuss conversion in more detail. We only consider “unsigned” numerals, i.e., non-negative numbers.

If we have an -digit unsigned numeral ... in radix (or base) , then the value of that numeral is

which is just fancy notation to say that instead of a 10’s or 100’s place we have an ’s or ’s place. For the three radices binary, decimal, and hex, we just let be 2, 10, and 16, respectively.

5.1Decimal Binary¶

The slidedeck below shows how we can convert the decimal 13 into its binary representation, 0b1101.

Let val be 13 in the explanation below. Click to show.

Explanation

Make columns 1, 2, 4, 8, which correspond to increasing integer powers of two. These columns also correspond to a 4-digit binary number, e.g., 0b _ _ _ _.

Take the largest power of two: , or eight. This “fits” into

val, so “use” it. “Using” means we need the binary digit1. Set the 4th-from-the-right space to1, i.e., populate0b 1 _ _ _. Because we have now “used up” eight, subtract it and updatevalto 5. This is the remainder we have to represent.Take the next power of two: , or four. “Use” it by setting the 3rd-from-the-right space to

1, i.e., populate0b 1 1 _ _. Updatevalto 1.Take the next power of two: , or two. We cannot “use” it because it is too big. “Not using” means we need the binary digit

0. Set the second-from-the-right space to0, i.e., populate0b 1 1 0 _.balis unchanged and is still 1.Take the next power of two, which is also the smallest: , or one. “Use” it by setting the rightmost space to

1, i.e., populate0b 1 1 0 1. Updatevalto 0.

The resulting binary string is 0b1101. By yourself, practice going the other way and check that 0b1101 represents the decimal number 13.

The process above relies on a few colloquial observations:

The largest power of two we could possibly need is less than the number

valitself.The smallest power of two we could possibly need is always the zero-th power, i.e., .

Start with larger power of twos first. Otherwise you may run into scenarios where you count beyond the number of digits available (here, only

0and1).

Here is one attempt at describing the algorithm to convert a number val into its binary representation:

Make a set of columns, one for each power of two. This corresponds to your -digit binary number, e.g.,

0b _ _ ... _ _, with blanks.Start from the leftmost column and go right (i.e., for from to 0, inclusive):

For the current column , corresponding to :

Is the current column less than or equal to

val?If yes, count how many fit into

val. For base 2, the count is1, so subtract fromval. Keep going.If no, put

0and keep going.

Stop this process once

valhits zero.

The point of this example is to teach you some tricks for converting between bases. Some students find the algorithmic description above more understandable than the mathematical description in Equation. If the latter makes more sense to you, then go for it.

5.2Decimal Hexadecimal¶

The slidedeck below converts 165 into its hexadecimal representation, 0xA5.

Let val be 165 in the explanation below. Click to show.

Explanation

Make columns 1, 16, 256, 4096 which correspond to increasing integer powers of sixteen. These columns also correspond to a 4-digit binary number, e.g., 0x _ _ _ _.

Take the largest power: . This does not fit into

val, so we set the 4th-from-the-right space to0, e.g.,0x 0 _ _ _.Take the next power: . This does not fit into

val, so we set the 3rd-from-the-right space to0, e.g.,0x 0 0 _ _.Take the next power: . Count how many times you can “use” it; at most ten 16’s fit into

val, which is currently 165. Ten is the hexadecimal digitA, so we set the 2nd-from-the-right space toA, e.g.,0x 0 0 A _. Subtract from 165 and updatevalto 5.Take the next power, which is also the smallest: , or one. Count how many times you can “use” it; at most five 1’s fit into

val, which is currently 5. Se the rightmost space to5, e.g.,0x 0 0 A 5. Updatevalto 0.

The resulting hexadecimal numeral is 0x00A5, or equivalently, 0xA5 if we dropped leading zeros.

You may have noticed that we included 163 and 162, which are both too large for representing 165. This is to show you that leading zeros are alright and can be dropped once you have gotten your result.

We leave it to you to translate the binary conversion process we described colloquially into a hexadecimal conversion process.

5.3Binary Hexadecimal Is Straightforward¶

Given the above, consider the following process for converting to binary to hexidecimal, which composes the processes we’ve discussed above:

Convert binary to decimal.

Convert decimal to hexadecimal.

This process is tedious—computing powers of twos is doable, but does every computer architect memorize powers of sixteen? Instead, we can directly convert between binary and hexadecimal with the observation:

There exists a one-to-one mapping between the set of hexadecimal digits and the set of length-four binary strings.

The above observation implies that a -length binary string can be translated into a -length hexadecimal string by independently converting each length-4 binary string into a hexadecimal digit, then concatenating the result. (We leave the proof of this to those of you that are enthusiastic mathematicians.) This makes conversion between binary and hexadecimal much easier:

To convert 0x1E to binary:

1in hexadecimal is0001in binaryEin hexadecimal is1110in binaryConcatenate:

0001 1110(we include the spaces to make visualizing easier)Drop leading zeros and compress spaces. (Optional) Add the

0bprefix to denote binary:0b11110

To convert 0b11110 to hexadecimal:

First group into full 4-bit strings, left-padding with zeros where necessary:

0001 11100001in binary is1in hexadecimal1110in hexadecimal isEin hexadecimalConcatenate:

0x1E(we add the0xprefix to denote hexadecimal)

6The computer knows it, too¶

At this point, it’s worthwhile to remind first-time readers that the two-character prefix 0b and 0x denote that the digits should be interpreted as binary and hexadecimal representations, respectfully. The 0 in 0b and 0x doesn’t mean anything by itself.

These prefixes allow computers to parse strings of digits and interpret them in their intended base.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

const int N = 1234;

printf("Decimal: %d\n",N);

printf("Hex: %x\n",N);

printf("Octal: %o\n",N);

printf("Literals (not supported by all compilers):\n");

printf("0x4d2 = %d (hex)\n", 0x4d2);

printf("0b10011010010 = %d (binary)\n", 0b10011010010);

printf("02322 = %d (octal, prefix 0 - zero)\n", 0x4d2);

return 0;

}Output:

Decimal: 1234

Hex: 4d2

Octal: 2322

Literals (not supported by all compilers):

0x4d2 = 1234 (hex)

0b10011010010 = 1234 (binary)

02322 = 1234 (octal, prefix 0 - zero)We don’t expect you to understand this code at this time. We will discuss C syntax, compilers, literals, etc. very soon. We also will not cover octal literals in this course; most standard C compilers will recognize hexadecimal and binary literals.

7Which base do we use?¶

Remember that there is only ever one number; this value that can be represented in multiple ways. The below are all representations of the same number, thirty-two:

3210, or simply 32. We recommend you write if you’re writing by hand.

0x20, or the hexadecimal numeral200b10000, or the binary numeral100002016. We recommend if you’re writing by hand.

100002. We recommend if you’re writing by hand.

Different representations serve different purposes:

Decimal: Great for humans, especially when doing arithmetic. We hope you won’t ever forget base-10 :-)

Binary: What computers use. To a computer, numbers are stored as binary data, regardless of how numbers are specified.

Hex: Hopefully you have realized by now that long strings of binary numbers are hard to parse. Hexadecimal is terrible for arithmetic on paper, but it is much more compact than binary while also being much much easier than decimal as a more compact way of representing binary values.

We use two strategies in this course to more easily visualize strings of 32 bits, 64 bits, etc.:

Group 4 bits at a time, e.g.,

0b0011 1010Convert each group of 4 bits to its hexadecimal digit, e.g.,

0x3A

Above all, remember that computers operate in binary, but humans don’t. So it’s good to get more comfortable with converting between these representations before we move further.