1Learning Outcomes¶

Write assembly to perform arithmetic operations.

Write arithmetic instructions involving immediates.

Understand how pseudoinstructions and the zero register help balance a reduced instruction set with flexibility of operations.

🎥 Lecture Video: add/sub

add/sub🎥 Lecture Video: Immediates

2add and sub Instructions¶

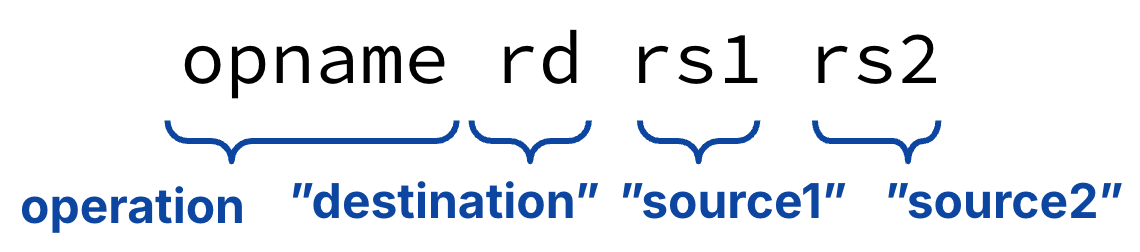

Generally, assembly instructions have a very rigid format. Consider arithmetic and logic instructions like addition (add), bitwise AND (and), etc., which operate on two registers and store the result in a third register. These instructions always follow the same rigid syntax shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1:R-Type instructions (arithmetic and logic involving two source registers).

The fields are separated by spaces[1], in order:

opname: The operation namerd: The destination register, i.e., the operand to which we store the result of the operation.rs1: The “source1” register, i.e., the first source operand for the operation.rs2: The “source2” register, i.e., the second operand for the operation.

The full set of instructions that follow the format in Figure 1 are located on the RISC-V green card. For now, we focus on two instructions in Table 1:

Table 1:The add and sub instructions.

| Instruction | Name | Description[2] |

|---|---|---|

add rd rs1 rs2 | ADD | R[rd] = R[rs1] + R[rs2] |

sub rd rs1 rs2 | SUBtract | R[rd] = R[rs1] - R[rs2] |

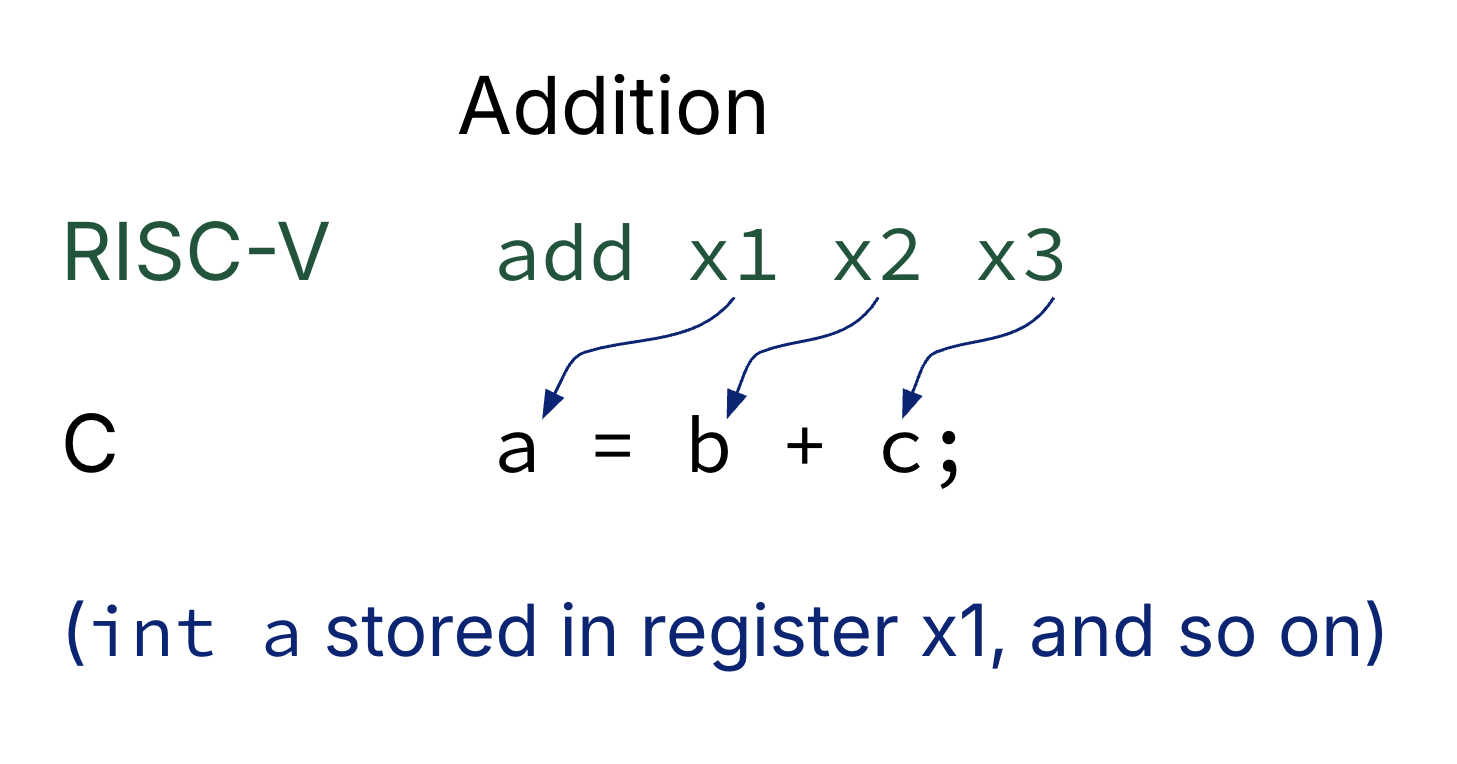

The addition command in assembly is simply add, which is easy to remember. The RV32I instruction

add x1, x2, x3is equivalent to the C statement a = b + c; for 32-bit integers[3] a, b, and c, where each variable corresponds to a value stored in a register. In Figure 2, the variable a is in register x1, variable b is in register x2, and variable c is in x3.

Figure 2:Addition instruction add in RISC-V and C.

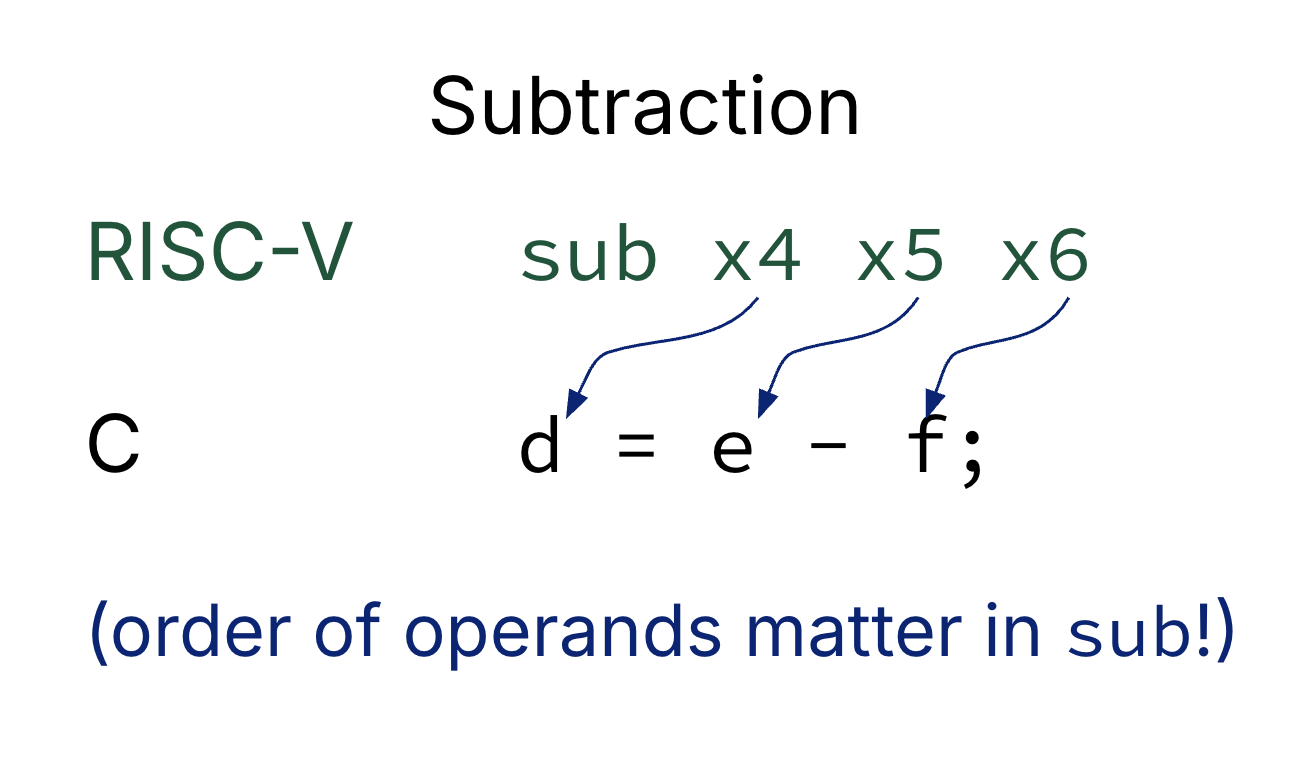

Subtraction works almost the same way, using the operation sub. If you want to subtract the values in x4 and x5 and store the result in x3, you would write the below, which is equivalent to the C integer arithmetic statement d = e - f; (Figure 3).

sub x3, x4, x5

Figure 3:Subtraction instruction sub in RISC-V and C.

2.1RISC Arithmetic: Examples¶

As mentioned earlier, a single line of C may translate into several lines of RISC-V. Consider the C integer arithmetic statement:

a = b + c + d - e;Suppose that variables a, b, c, d, and e mapped to registers x10, x1, x2, x3, and x4, respectively. We can use x10 as a running sum to compute the correct value of a after three instructions:

add x10 x1 x2 # a_temp = b + c

add x10 x10 x3 # a_temp = a_temp + d

sub x10 x10 x4 # a = a_temp - eShow Answer

Both solutions are valid. Tradeoffs:

Approach A uses temporary registers

x5andx6and more directly follows the C order of operations. However, any existing data in registersx5andx6will now be overwritten.Approach B leverages algebra to avoid any temporary registers. For more complicated algebra (e.g., distributing a multiply), we may need more clever compilers.

3Immediates¶

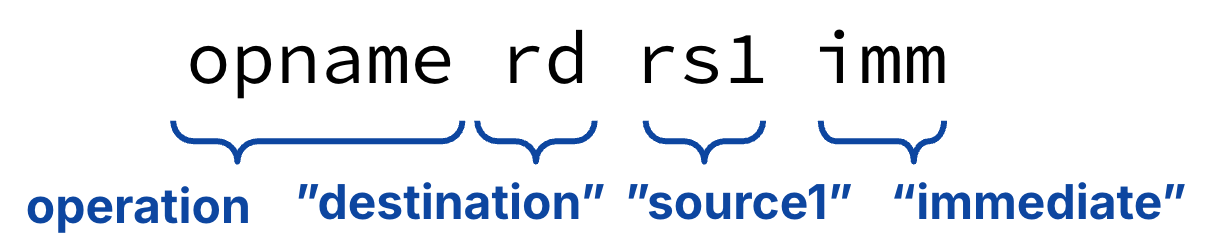

Immediates are numerical constants in RISC-V. Immediates are called as such because their bit patterns are directly encoded into the machine instruction—thus their values are “immediately” available to the computer.

Immediates appear often in code; hence, they have separate instructions (Figure 5).

Figure 5:Arithmetic and Logical I-Type instructions involving one source register and one immediate.

Like before, fields are separated by spaces[1], in order:

opname: The operation namerd: The destination register, i.e., the operand to which we store the result of the operation.rs1: The “source1” register, i.e., the first source operand for the operation.imm: The immediate (numeric constant).

The full set of instructions that follow the format in Figure 5 are located on the RISC-V green card.

3.1addi instruction¶

Let’s discuss the Add Immediate instruction (Table 2).

Table 2:The addi instruction.

| Instruction | Name | Description[2] |

|---|---|---|

addi rd rs1 imm | ADD Immediate | R[rd] = R[rs1] + imm |

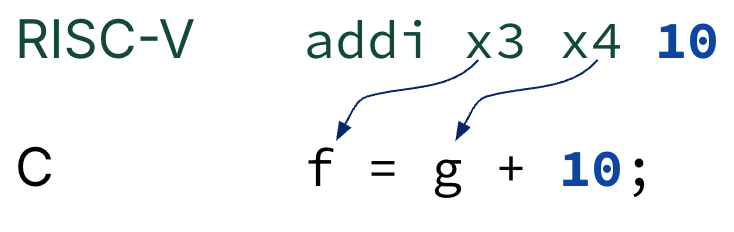

The RV32I instruction

addi x3, x4, 10is equivalent to the C statement f = g + 10;, where f and g are 32-bit integers (Figure 6).

Figure 6:Add immediate instruction in RISC-V and C.

4Using x0 to reduce our instruction set¶

We have previously discussed the zero register x0. Hardwiring register x0 to the value zero proves extremely useful for reusing add and addi for very common C operations.

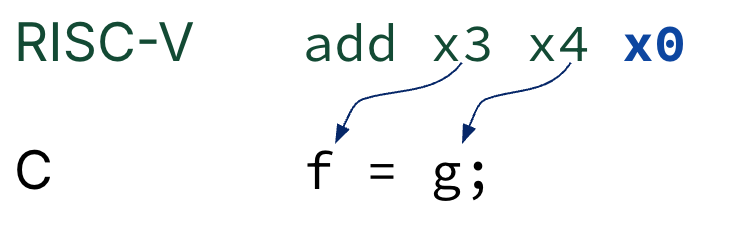

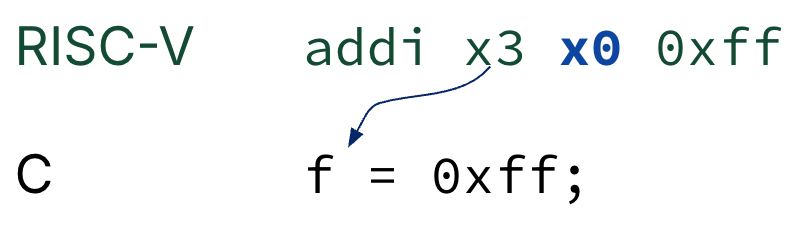

Two toy examples are shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9:

Figure 8:To assign the C integer variable f to the value of another integer variable g, we could use add with x0 as a source operand (though we don’t in practice[4]).

Figure 9:To assign the variable f to a numeric constant, use addi with x0 as the source register operand.

5Pseudoinstructions¶

We have just seen several cases where common C statements translate into other instructions in our reduced instruction set architecture. While this is fine and dandy for designing architecture, compilers (and you, as a human assembly instruction-writer) will find it useful to use pseudoinstructions.

Pseudoinstructions are convenient instructions in RISC-V. Pseudoinstructions help compilers more directly translate higher-level language code into assembly instructions (really!), but by themselves they are not real instructions.

Consider two examples below (and see the full set in the RISC-V green card).

Table 3:The subset pseudoinstructions.

| Pseudoinstruction | Name | Description | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

mv rd rs1 | MoVe | R[rd] = R[rs1] | addi rd rs1 0[4] |

li rd imm | Load Immediate | R[rd] = imm | addi rd x0 imm[5] |

nop | No OPeration | do nothing[6] | addi x0 x0 0 |

When assembling to machine instructions, the assembler replaces pseudoinstructions with their real instruction counterpart.

Why

addiwith immediate0and notaddwithx0(as in Figure 8)? See the ASM manual on GitHub.This description is incomplete given the range of

imminaddi. See the green-card and future sections for the full translation of load immediates.We will see later how a “no-op” instruction can improve hardware performance (really).