1Learning Outcomes¶

Know terminology: RISC, CISC, ISA.

Understand that at a high level, RISC architectures support a simple instruction set with fast hardware.

🎥 Lecture Video

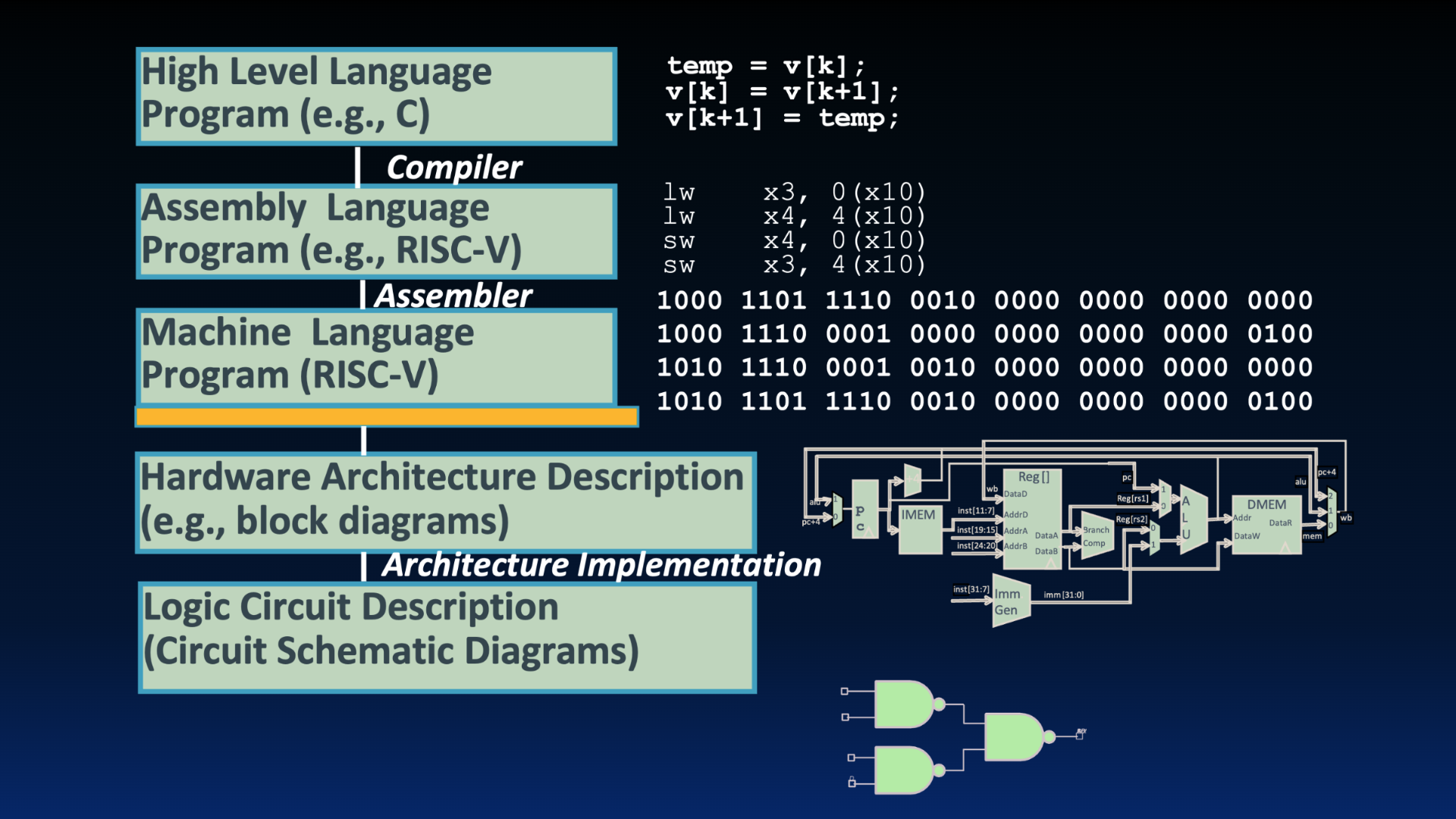

We are going to dive down to the next level of abstraction and cover the RISC-V instruction set architecture and the RISC-V assembly language. Early in the class, we discussed The Great Idea of Abstraction (Figure 1): layering different levels of abstraction to represent complex compute systems.

Figure 1:Great Idea #1: Abstraction.

At the top, there is a high-level language (like C). Below that is the assembly language; below that is the machine code (the machine-readable version); and below that are implementations like block diagrams. Even further down, we find logic gates, which are built then out of transistors.

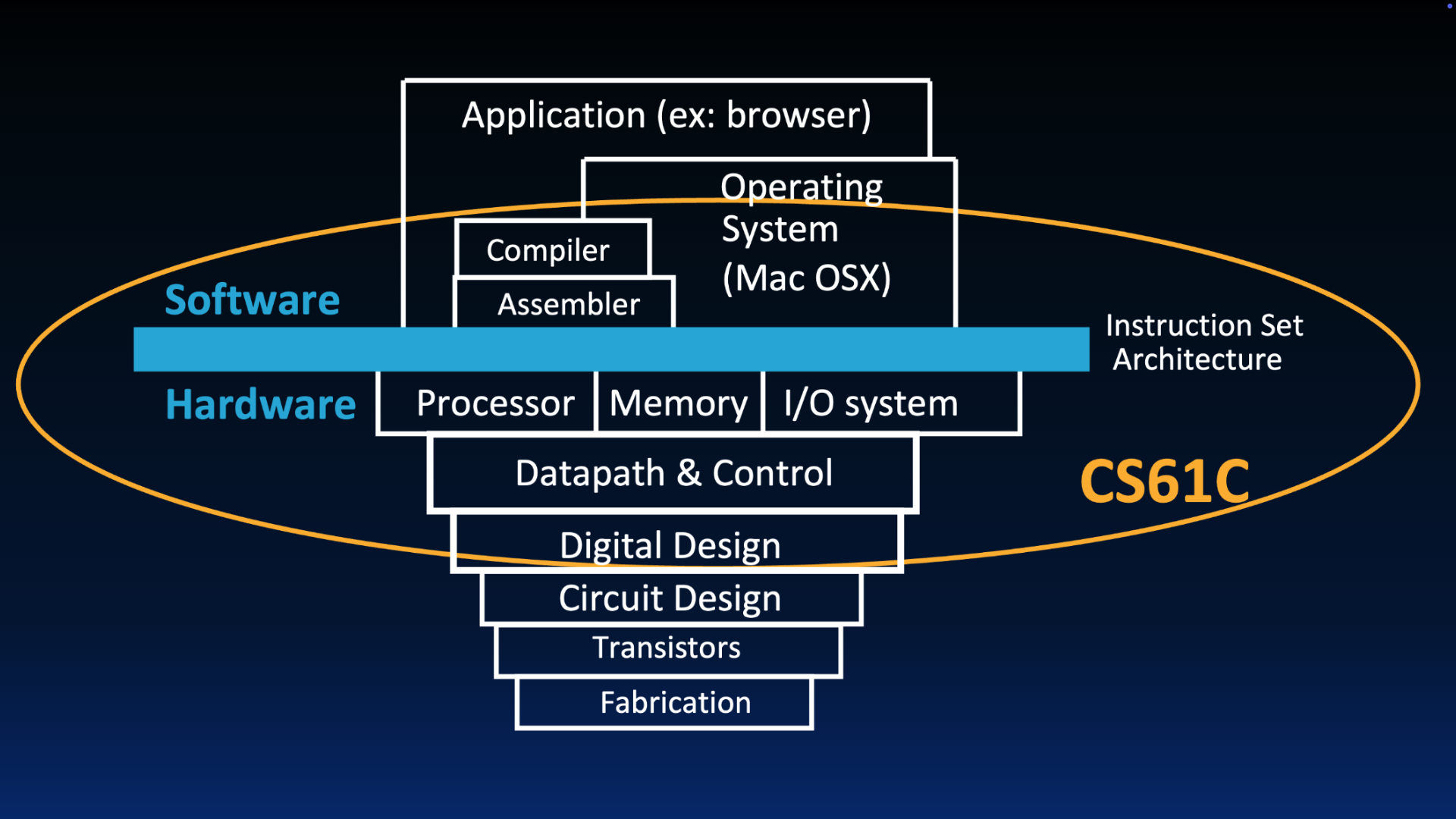

There are always well-defined interfaces between these layers. In this unit, we focus on the instruction set architecture (Figure 2), which defines how software interfaces with hardware.

Figure 2:Great Idea #1: Abstraction.

From Wikipedia:

In general, an ISA defines the instructions, data types, registers, and the programming interface for managing main memory such as addressing modes, virtual memory, and memory consistency mechanisms. The ISA also includes the input/output model of the programmable interface

On one side, the ISA is used as a standard by which we design and write instructions. On the other side, the ISA is used as a standard by which we design computers and hardware (e.g., CPUs). Instructions written according to an ISA can then be executed by computers designed according to that same ISA.

1.1Why learn assembly?¶

In practice, it is rare that we would write assembly language code ourselves. Most commonly, assembly language is produced by a compiler. An assembler then produces the machine-readable code.

So why learn assembly?

Consider this excerpt of a 2004 post from the forum site slashdot.org:

A new book was just released which is based on a new concept - teaching computer science through assembly language (Linux x86 assembly language, to be exact). This book teaches how the machine itself operates, rather than just the language. I’ve found that the key difference between mediocre and excellent programmers is whether or not they know assembly language. Those that do tend to understand computers themselves at a much deeper level. Although unheard of today, this concept isn’t really all that new -- there used to not be much choice in years past. Apple computers came with only BASIC and assembly language, and there were books available on assembly language for kids. This is why the old-timers are often viewed as ‘wizards’: they had to know assembly language programming. Perhaps this current obsession with learning using ‘easy’ languages is the wrong way to do things. ..."

Understanding assembly means understanding how the computer executes instructions. By doing so, we can write programs in higher-level languages that are high-performing, resource-efficient, and cost-effective.

2RISC vs. CISC¶

Different CPUs implement different ISAs:

x86: Intel i9, i7, i5, i3, and many AMD processors

ARM: Used in many cell phones; also the basis of the Apple silicon series

MIPS, as of 2020 deprecated in favor of

RISC-V: The focus of our course.

In the early 1970s and 1980s, there was a trend to build more and more complex instructions for computers. After all, the world was software! Each instruction would do multiple tasks, like accessing memory and performing arithmetic simultaneously. These complex instruction sets could reduce the size of programs and even the number of memory accesses per program. However, the resulting hardware needed to implement these instruction sets was often more complex to design and expensive to implement. Retroactively, these architectures were called Complex Instruction Set Computers (CISC).

In the early 80s, a different idea emerged from John Cocke, who designed the IBM 801. This was the first reduced instruction set computer (RISC): Keep the instruction set small and simple. Complexity was pushed into the software and compiler to compose complicated operations using these simple instructions. This simpler layer made it much easier to build faster hardware!

The RISC[1] idea caught on quickly: A given program now would require more assembly instructions but still execute faster than before if the corresponding hardware could be designed to execute many more instructions per second.

This idea was then taken to its full extent by Professors Dave Patterson at UC Berkeley and John Hennessy at Stanford. These two labs developed two very similar projects simultaneously: the RISC project (at UC Berkeley) and the MIPS project (at Stanford). RISC processors were used for a multitude of microprocessor architectures.

Ultimately, both RISC and CISC (i.e., “not RISC” architecture) are still relatively popular. Both architecture paradigms in rapid development, and industry designs are still racing to improve performance. In the market, many Microsoft-based computers purchase Intel architectures; recently, Apple has developed its own ARM-based silicon.

3Why RISC-V?¶

When teaching, we have to choose an ISA. x86 is very complex, while older or “made-up” ISAs often lack a real software stack or compilers.

The RISC-V[2] ISA was developed in 2010 at UC Berkeley. After its emergence about 10 years ago, it has been used to develop all levels of computing systems, from microcontrollers in embeded systems to warehouse-scale supercomputers. It supports many processor variants–most commonly, 32-bit, 64-bit, and 128-bit.

RISC-V is extremely popular for two primary reasons: It is open-source and license-free. Anyone can use it without paying rights, making it popular for teaching[3], research, and commercial use. The RISC-V development is supported by a growing shared, international ecosystem[4] of academic and industry leaders. The entire definition of the RISC-V architecture fits on a single page called the “Green Card,”[5] named after the famous IBM 360 green card from the 1960s.

We teach RISC-V in our class because it is simple and elegant–both for understanding assembly language and for designing computer architecture. Go Bears :-)

Professors Patterson and Krste Asanoviç began the RISC-V project in 2010 as part of the Par Lab to develop open research and teaching at UC Berkeley. One of the project outputs was a four-course sequence for undergradate and graduate students, which eventually developed into our UC Berkeley computer architecture curriculum today. Read more on the RISC-V About page and in the RISC-V Genealogy Report.

The “RISC-V green card” in these course notes is longer than one page, due to the accessible web format. For a two-sided reference card with the same information, check out the PDF reference card on our course website.