1Learning Outcomes¶

Understand the limits of a “fixed point” representation of numbers with fractional components.

Compute range and step size for integer and fixed-point representations.

Identify limitations of fixed-point representations.

🎥 Lecture Video

Learning architecture means learning binary abstraction! Let’s revisit number representation. Now, our goal is to use 32 bits to represent numbers with fractional components—like 4.25, 5.17, and so on. We will learn the IEEE 754 Single-Precision Floating Point standard.

To start, I want to share a quote from James Gosling (the creator of Java) from back in 1998.[1]

“95% of the folks out there are completely clueless about floating-point.”

You will be in the 5% after this chapter :-)

2Metrics: Range and Step Size¶

Recall that N-bit strings can represent up to distinct values. We have covered several N-bit systems for representing integers so far, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1:A subset of the N-bit integer representations we have discussed in this class.

| System | # bits | Minimum | Maximum | Step Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unsigned integers | 32 | 0 | , i.e., | 1 |

| Signed integers with two’s complement | 32 | 231, i.e., | , i.e., | 1 |

The range of a number representation system can be quantified by computing the minimum representable and maximum representable numbers. Just like with integer representations we will explicitly compute the range and compare it with some target application. In Table 1, we see that unsigned integers give a maximum that is about twice that of two’s complement—because the latter allocates about half of its system to representing negative numbers.

The step size of a number representation system is defined as the spacing between two consecutive numbers. For integer representations that we consider in this class, step size is always 1 between consecutive integers. On the other hand, with fractional number representations we will not be able to represent the infinite range of (real) numbers between two consecutive numbers, hence step size becomes an important metric of precision.[2]

3Fixed Point¶

Let’s motivate floating point by first exploring a strawman[3] approach: fixed point. A “fixed point” system fixes the number of digits used for representing integer and fractional parts.

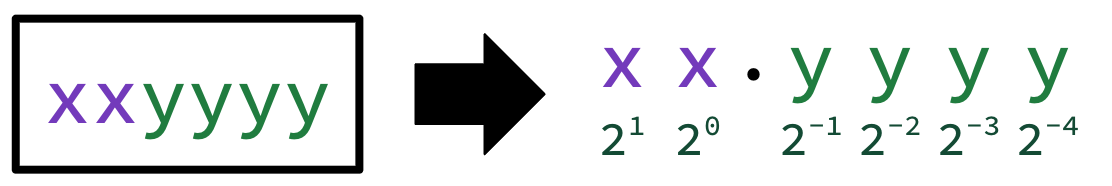

Think back to when you first learned the decimal point. To the left of the point, you have your 1s (100), 10s (101), 100s (102), and so on. To the right of the point, the numbers represent tenths (10-1), hundredths (10-2), thousandths (10-3), and so on. The binary point functions similarly for a string of bits. To the left of the binary point are powers of two: 1 (20), 2 (21), 4 (22), and so on. To the right of the binary point are negative powers of two: 1/2 (2-1), 1/4 (2-2), 1/8 (2-3), and so on.

A 6-bit fixed-point binary representation fixes the binary point to be a specific location in a 6-bit bit pattern. Consider the 6-bit fixed-point representation shown in Figure 1. This fixes the binary point to be 4 bits in from the right, and assumes that we only represent non-negative numbers.

Figure 1:Under this 6-bit fixed-point representation, number 2.625

Under this system, the number 2.625 has bit pattern 101010:

3.1Fixed Point: Range and Step Size¶

Show Answer

Range:

Smallest number

000000: zero.Largest number:

111111, or 3.9375 =

Show answer

The smallest fractional step we can take is incrementing the least significant bit, which is .

3.2Arithmetic¶

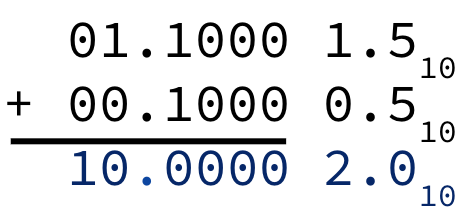

Figure 2 shows that fixed-point addition is simple. By lining up the binary points, fixed-point formats can reuse integer adders.

Figure 2: using the 6-bit fixed point representation from Figure 1.

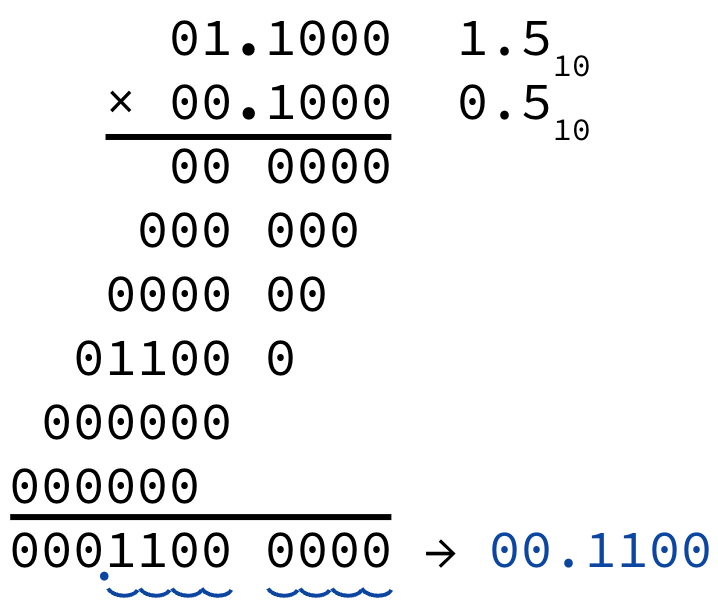

However, Figure 3 shows that fixed-point multiplication is more complicated. Just like in decimal multiplication, we must shift the binary point based on the number of fractional digits in the factors.

Figure 3: using the 6-bit fixed point representation from Figure 1.

3.3Use Cases¶

Fixed point representations are very useful in specific domains that prefer very fast computation of values with specific characteristics. Some graphics applications prefer fixed-point for fast calculations when rendering pictures.

4Scientific Numbers¶

Developers considered what was needed to define a number system that could represent the numbers used in common scientific applications:

Very large numbers, e.g., the number of seconds in a millenium is

Very small numbers, e.g., Bohr radius is approximately meters

Numbers with both integer and fractional points, e.g., 2.625

A fixed-point representation that could represent all three of these example values would need to be at least 92 bits[4], which is much larger than the 32-bit integer systems discussed in Table 1.

The problem with fixed point is that once we determine the placement of our binary point, we are stuck. In our six-bit representation from Figure 1, we have no way of representing numbers much larger than 3.975 or numbers between, say, 0 and , much less the many numbers in across scientific applications.

What if we had a way to “float” the binary point around and instead choose its location depending on the target number? Developers of the IEEE 754 floating point standard found a solution in a very common scientific practice for denoting decimal numbers: scientific notation. Let’s read on!

From a keynote talk delivered by James Gosling on February 28, 1998. The original link is lost, but Professor Will Kahan’s “How Java’s Floating-Point Hurts Everyone Everywhere” gives reasonable context for Gosling’s talk, proposal, and alternatives.

We will define precision properly soon; for now, consider precision a metric of our representations’s ability to represent small changes in numbers.

needs 34 bits for the integer part, and needs 58 bits for the fractional part.